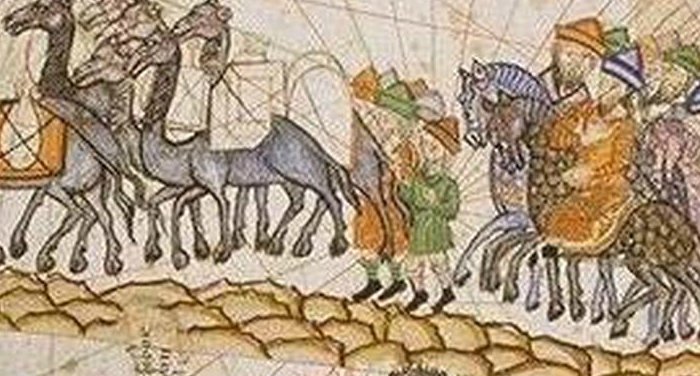

Indian e-commerce: Profits via silk route?

As I spent time talking to business journalists and leading industry players on the side-lines of a global event in India recently, one question hogged the discussion more than any other – how sustainable is the e-commerce boom in India?

As I spent time talking to business journalists and leading industry players on the side-lines of a global event in India recently, one question hogged the discussion more than any other – how sustainable is the e-commerce boom in India?

Clearly, India’s e-commerce players continue to grow at a blistering pace, with growth rates of 50-55% p.a. in the past few years beating all expectations and blowing past challenges like low broadband and smartphone penetration, limited banking and digital payments penetration and poor logistics infrastructure.

Still, many wonder how – and when – key players will find the path to profitability. Some observers despair that this amazing growth story is fueled by the steroid-like effect of discounts, and when that effect fades, so will the e-commerce wave.

By contrast, Chinese e-commerce has truly come of age and is now leading the world, not only in scale but also in innovation. Importantly, it is profitable, too! Can Indian e-commerce travel along the “silk route” to significant profits by taking on board lessons from China? If so, how long will the journey to profitability take?

What can India learn from the success of Chinese e-commerce?

Before we compare the development of e-commerce in the two Asian giant economies, we must recognize and address the enormous difference in scale. Despite its incredible growth, Indian e-commerce is projected to be about USD 35 bn by 2020. The Chinese e-commerce industry is about 20 times that much today! No surprise then that the e-commerce economics of the two countries are very different.

A more useful comparison would be between the relative unit economics of e-commerce in the two countries, i.e. to assess whether Chinese e-commerce economics are better on a per customer basis. Generally speaking, the answer to this is “yes”. What drives better unit economics in Chinese e-commerce and can India replicate those drivers to create better economics? In my mind, (at least) three key drivers of better economics in Chinese e-commerce are not fully leveraged by Indian players.

1. Better business model Most of Chinese e-commerce GMV is driven through the B2B2C – or marketplace – business model. Being asset-light, this model’s economics are far superior to the inventory-based e-commerce model that still accounts for the bulk of India’s e-commerce GMV. As Indian players are in the process of migrating rapidly to marketplace business models, their unit economics are bound to improve as a result of this shift.

2. More revenue streams Leading Chinese players have succeeded in monetizing multiple revenue streams (online sales commission, advertising, payments and Logistics as a Service), leading to higher revenue per transaction. Once again, Indian players are rapidly catching up in this area as well and as they continue to focus on this, unit economics will improve.

3. Better merchant ecosystem Leading Chinese players have over a million merchants in their marketplaces, leading to a dizzying array of choice for the consumer. By contrast, Indian e-commerce players have only a 100,000 or so and even these often offer a smaller range and some suffer from quality issues, affecting the user experience negatively. Upgrading the merchant ecosystem – both in quantity and quality – will allow for better conversion rates per site visitor, larger basket size per sale and better loyalty rates, resulting in much higher customer lifetime value (CLV). In this sense, this is perhaps the most significant long-term driver of better economics and is currently under-leveraged by Indian e-commerce players. Investing in merchant facilitation and enablement will be a big driver of the sector in the years to come.

My conversations with Indian e-commerce executives suggest that they are working hard to address these systemic issues and if they maintain this focus, their economics should improve in the next few years. The direct participation of sophisticated US and Chinese players in the Indian e-commerce market will drive the sector even faster in this direction.

Will the Indian e-commerce consumer mature?

As valid as the above points may be, their effect will come to naught if the hypothesis remains that the Indian e-commerce shopper buys only for the discounts, which will have to wear off at some time. My colleagues in EY India recently published an insightful report investigating this issue via market analysis and a survey of over 700 respondents across India, and here are some of their key messages:

1. Target the right consumer There is no doubt that so far, Indian e-commerce has operated mostly in a “land grab” mode, essentially buying consumers with mouth-watering discounts. There is also no doubt that this strategy is not sustainable in the long-term. As my colleagues put it: “… not only does it dent profitability, but also results in disloyal buyers who merely seek the best bargains.” The survey shows that 61% shoppers might stop buying if there are no discounts, but it also shows that 40% consumers say convenience – and not price – is the #1 reason they buy online. Focusing on these consumers will be key for sustainable success.

2. Better segmentation So far, the e-commerce shopping experience in India is largely undifferentiated, and this needs to change. Profitable segments (like middle-aged professionals, career women and affluent rich in Tier 2/3 cities) have been overlooked in the mad rush for generic subscriber acquisition and GMV. Developing deep insights into these segments would allow Indian players to offer products, offers and shopping experiences that best meets their needs, thus driving valuable transactions and creating high-value, loyal shoppers.

3. Digital payments CoD (Cash on delivery), initially hailed as an innovative mechanism to drive e-commerce development in India, has now become an albatross around the sector’s neck, due to high costs, including leakage. CoD transactions account for around 60% of overall sales in the Indian e-commerce market, much higher than in China (40%), Indonesia (28%) and the US (2%).

When will India get there?

The “silk route” does show a clear path to profitability and the Indian consumer – or at least a large segment – is willing to come along for the ride. But how long will it take for India to have a sustainable, profitable, e-commerce sector?

In my view, the environment for the growth of e-commerce in India could not be more favorable in the next few years. A firm governmental effort to bring more of India’s population into the banking system via the Jan Dhan program; a clear intent to move to a cashless, formal transaction economy via bold moves like the recent demonetization effort; a burgeoning and innovative fintech sector and a fast growing broadband and smartphone ecosystem are all likely to help the “e-tail” sector. So will more clear and favorable regulations for the sector and more mature operating models that bring traditional retailers along as logistics or click-and-collect partners instead of viewing them as adversaries.

On the flip side, in terms of logistics infrastructure, China’s urban infrastructure, even in smaller cities, has so far been vastly superior to India’s and proved a significant contributor to its e-commerce success. So did the fact the China’s merchants ecosystem is much bigger and better enabled. And Chinese e-commerce is now growing by going global, which India is yet to do on any meaningful scale.

Analyses across many categories and sectors over the years have shown that the India-China lag in category or sector development ranges from five to twenty years. In my view, India is perhaps a bit more than ten years behind China in e-commerce development, and I think India is poised to have a large, sustainable, profitable, locally relevant and globally competitive e-commerce sector in or soon after 2025.