Global competitiveness: what makes an economy great?

Like it does every year, the Davos-based World Economic Forum (WEF) has recently released its Global Competitiveness Report for this year. Since its launch in 2005, the WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) has been the basis of this ranking of nations, and while the theoretical basis is only moderately robust in my opinion, there is no doubt that the GCI has come to be widely recognized as the best available measure of the relative competitiveness of a nation’s economy. Not surprisingly then, these rankings tend to sought after, eagerly awaited and sometimes hotly debated every year when they arrive.

Like it does every year, the Davos-based World Economic Forum (WEF) has recently released its Global Competitiveness Report for this year. Since its launch in 2005, the WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) has been the basis of this ranking of nations, and while the theoretical basis is only moderately robust in my opinion, there is no doubt that the GCI has come to be widely recognized as the best available measure of the relative competitiveness of a nation’s economy. Not surprisingly then, these rankings tend to sought after, eagerly awaited and sometimes hotly debated every year when they arrive.

Of the 144 countries that participated in the ranking this year, Switzerland comes out on top for the sixth year in a row and Singapore takes the #2 slot for the fourth consecutive year. In this sense, there are no major surprises in the latest version. However, it is worth reflecting on why we end up with what is by now a fairly consistent picture of global competitiveness and how these results stack up against our generally held views on what makes nations great. Even a little reflection can surface some rather interesting issues, which are the focus of this post.

Three stages of competitiveness

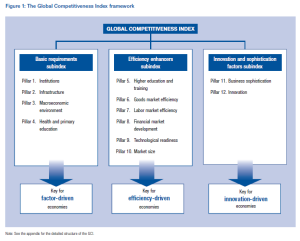

As seen in the chart on the right, WEF economists have theorized that the competitiveness of an economy is a function of 12 “pillars”, which include things you would reasonably expect to measure like the quality of its infrastructure, the robustness of its institutional framework, social infrastructure, market transparency, technological readiness and the like. Scores on each of these pillars are laboriously calculated for each nation and then combined (with a weighted average logic) to arrive at a country’s GCI score, and the global ranking is then determined based on the relative scores.

As seen in the chart on the right, WEF economists have theorized that the competitiveness of an economy is a function of 12 “pillars”, which include things you would reasonably expect to measure like the quality of its infrastructure, the robustness of its institutional framework, social infrastructure, market transparency, technological readiness and the like. Scores on each of these pillars are laboriously calculated for each nation and then combined (with a weighted average logic) to arrive at a country’s GCI score, and the global ranking is then determined based on the relative scores.

What is more interesting is that these 12 pillars of competitiveness are grouped into three categories:

- Basic factors like institutions and infrastructure which mostly drive Stage One or factor driven economies (e.g. India). These are typically less developed countries which compete in the world market on the basis of factor cost advantages like cheap labor or natural resources. In other words, these countries say to the world market, “I can provide the resources cheaper”.

- Efficiency factors like market transparency and quality of education which drive Stage Two or efficiency driven economies (e.g. China). As countries develop, they can no longer keep factor costs low and in order to remain competitive, they have to now improve efficiency and productivity. Their ability to do so drives the competitiveness of their economy at this stage of development more than the basic factors do. In other words, these countries say to the world market, “I can process resources more efficiently and hence do it cheaper”.

- Innovation factors like business sophistication which drive Stage Three or innovation driven economies (e.g. USA). Once efficiency factors plateau out, an economy’s competitiveness no longer depends on doing the same thing as everyone else, just cheaper. Rather, they need to find fundamentally new ways of doing things and/or doing entirely new things that are not done by others, i.e. they have to innovate to maintain their competitiveness at this stage. Most of the developed countries are obviously at this stage, and accordingly, the weightage of innovation factors is higher in their GCI computation.

The grouping of countries by these three stages of development (chart of the left) reflects the current structure of the world, with the least developed countries on the left and progressively more and more developed economies occupying the right side of that chart. What is more interesting about this grouping is that it introduces the concept of transitional economies. As you can imagine, it is by no means easy or automatic for a country to move from one stage – or one basis of competitiveness – to the next one. A factor driven economy that has long grown on the basis of, say, cheap labor (like the Philippines) or oil (like Kuwait) now needs to invest in mechanization and higher education to advance to the efficiency driven stage. This requires major shifts in policies, investments and programs. Similarly, an efficiency driven economy like Malaysia now needs to go beyond efficient mass production to create a culture of entrepreneurship, innovation and research and make the corresponding shifts in its policies, investments and programs to maintain its future competitiveness. The ability and the speed with which economies can make these critical transitions is a major determinant of the well-being of their future generations in the emerging world order.

The grouping of countries by these three stages of development (chart of the left) reflects the current structure of the world, with the least developed countries on the left and progressively more and more developed economies occupying the right side of that chart. What is more interesting about this grouping is that it introduces the concept of transitional economies. As you can imagine, it is by no means easy or automatic for a country to move from one stage – or one basis of competitiveness – to the next one. A factor driven economy that has long grown on the basis of, say, cheap labor (like the Philippines) or oil (like Kuwait) now needs to invest in mechanization and higher education to advance to the efficiency driven stage. This requires major shifts in policies, investments and programs. Similarly, an efficiency driven economy like Malaysia now needs to go beyond efficient mass production to create a culture of entrepreneurship, innovation and research and make the corresponding shifts in its policies, investments and programs to maintain its future competitiveness. The ability and the speed with which economies can make these critical transitions is a major determinant of the well-being of their future generations in the emerging world order.

The staging concept is very useful for policy makers to help set their priorities, but by no means should be taken to mean that early stage economies should not invest in developing advanced capabilities. Rather it only means that they should prioritize the basics (like infrastructure and primary healthcare) more, while slowly but surely developing on things like advanced technology and research.

What makes an economy great?

Having understood the key drivers of competitiveness (12 pillars) and their relative importance (depending on the stage of economic development) we have by now done the ranking of the world’s nations for a decade on these factors. This body of work has provided us with a fairly consistent world-view of how economic competitiveness stacks up globally. What can we conclude from all this work about what makes an economy great? Let us consider a few widely held notions:

- Territory: Over the course of centuries, millions of lives have been lost in territorial conflicts to lead to the world map being the way we find it in our times. Nations still take their territorial integrity very seriously and there are some good reasons for it, too. However, when it comes to economic excellence, territorial size does not seem to count for much. As many as five of the top 10 economies in the WEF ranking are between puny to small in size! Conversely, only one of the ten largest nations makes it to the top ten economies on this ranking. If anything, this tells us that countries are better off being smaller rather than larger for them to be economically competitive in the world of the future! Smaller, urbanized economies usually govern themselves better and with more transparency, manage risks and investments better, implement programs faster and are more effective in fostering productivity, education and innovation.

- Population: While national pride is often about the size of the population, a quick look reveals that some of the most populous nations (Bangladesh, India, Indonesia) are at the bottom of the heap when it comes to economic competitiveness, while those with meager populations (Switzerland, Singapore, Sweden, Finland) occupy the top slots. Increasingly in today’s world, it is not the population size, but rather the productivity and the innovation ability of the population – quality rather than quantity – that makes the difference.

- Resources: Sure, discovering a few billion barrels of oil on your land will help the economy. But this works – at best – only up to the first stage of economic development, i.e. the factor driven stage. To get beyond that stage, an abundance of natural resources is not of much use, and very often smarter economies benefit more from the natural bounty of poorer but resource-rich nations, the most classic example of this being African nations like Libya and Nigeria.

- Military: During the Cold War era, the former USSR sought world dominance mostly via military might. Russia’s current #53 rank does not bear strong testimony to that strategy. By contrast, #1 and #2 best performing economies (Switzerland and Singapore) are military light weights. Among the top ten competitive economies, only four are also among the top ten military powers. So while there is some correlation, it is weak to moderate.

Clearly, it seems like the old paradigm of competitive advantage of nations – having vast empires with large armies protecting large populations and hoarding vast resources – is increasingly irrelevant in the world of today and tomorrow. The days of “hard power” are (mostly) in the past. So what does – and will – make an economy great now and in the future? I would call it “soft power” but I would expand the notion beyond the original conception of Joseph Nye of Harvard, who coined the term more in the context of international relations (as opposed to macro-economic competitiveness). For the avoidance of confusion, I would call it Soft Power 2.0.

Soft power 2.0

Consider what it takes to be the best in the world on the WEF’s twelve pillars of economic competitiveness. It is about the ability to manage multiple stakeholders in an institutional framework that works fluidly with the right checks and balances, thereby maintaining a consistent and stable policy environment. Then, it is about creating trust and transparency around this integrated institutional framework and creating mechanisms for rapid program implementation, issue redressal and recourse. This is what causes global investments to pour in by the billions into small economies like Hong Kong, Singapore and Switzerland. It is about having the best educational institutions, the best research and development organizations and the most effective innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems. It is also about attracting global talent, global investment and skillfully maintaining peace and accord with the rest of the world. What is common among all these success factors? They are all about soft skills like managing stakeholders, orchestrating ecosystems and fostering the right spirit (trust and transparency) and culture (efficiency and innovation).

Taken collectively, these abilities are what I would call Soft Power 2.0, and in today’s world and even more so in the world of tomorrow, Soft Power 2.0 will separate the winning economies from the laggards.

I would love to read your thoughts and comments below. To download the full World Economic Forum report, please click here